Field Notes, Historiography, Objects, Practices, Technologies

Faunal Nature Printing: Traces of Life in Sherman Denton’s Moths and Butterflies (1900)

Nature self-printing (Naturselbstdruck) is a printing technique that consists in pressing the coloured surface of an object directly onto paper, hereby imprinting the page with a distinctive, non-reproducible image. In this article, 4A_Lab Fellow Judith Elisabeth Weiss traces the history and development of nature prints, highlighting some crucial issues in 19th-century discourses around nature, aesthetics, and art.

13.01.2022

Find the German version of this text here.

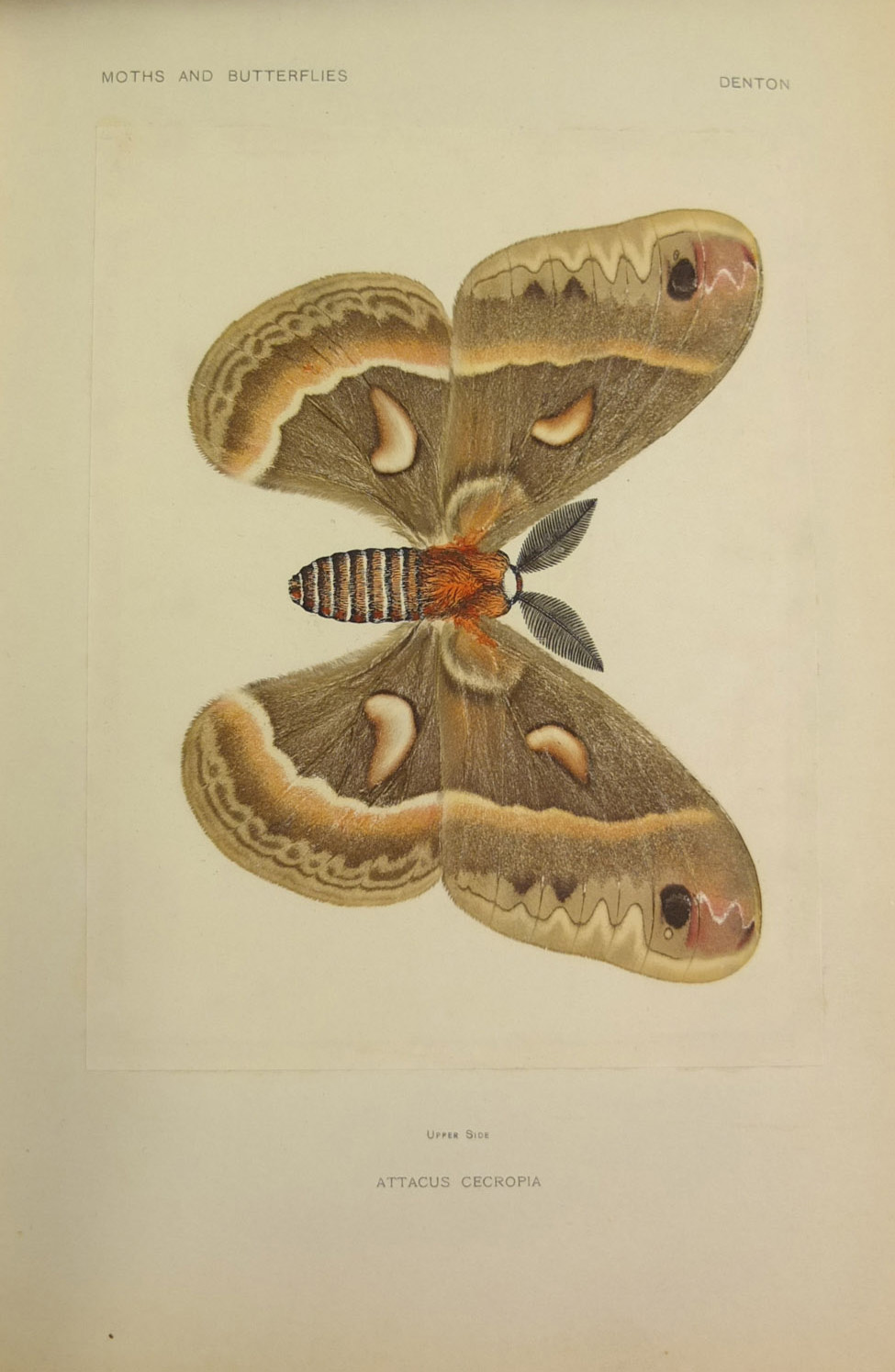

In 2007, the Historical Prints Department of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin State Library, SBB) acquired an extraordinary item for its Special Collections: an edition of Sherman F. Denton’s (1856–1937) two-volume work As Nature Shows Them. Moths and Butterflies of the United States. East of the Rocky Mountains, published in Boston in 1900 (call number: 50 MB 6407-1/2: R). The Berlin copy is number 25 in a limited edition of just 500 pieces. Despite the rather unspectacular title, the two volumes are sumptuous in appearance—with gold edges and a magnificently decorated leather binding. In addition to more than 400 black-and-white photographs and countless drawings of moths and butterflies, each piece in the edition brings together a considerable number of nature self-prints, and is thus unique.

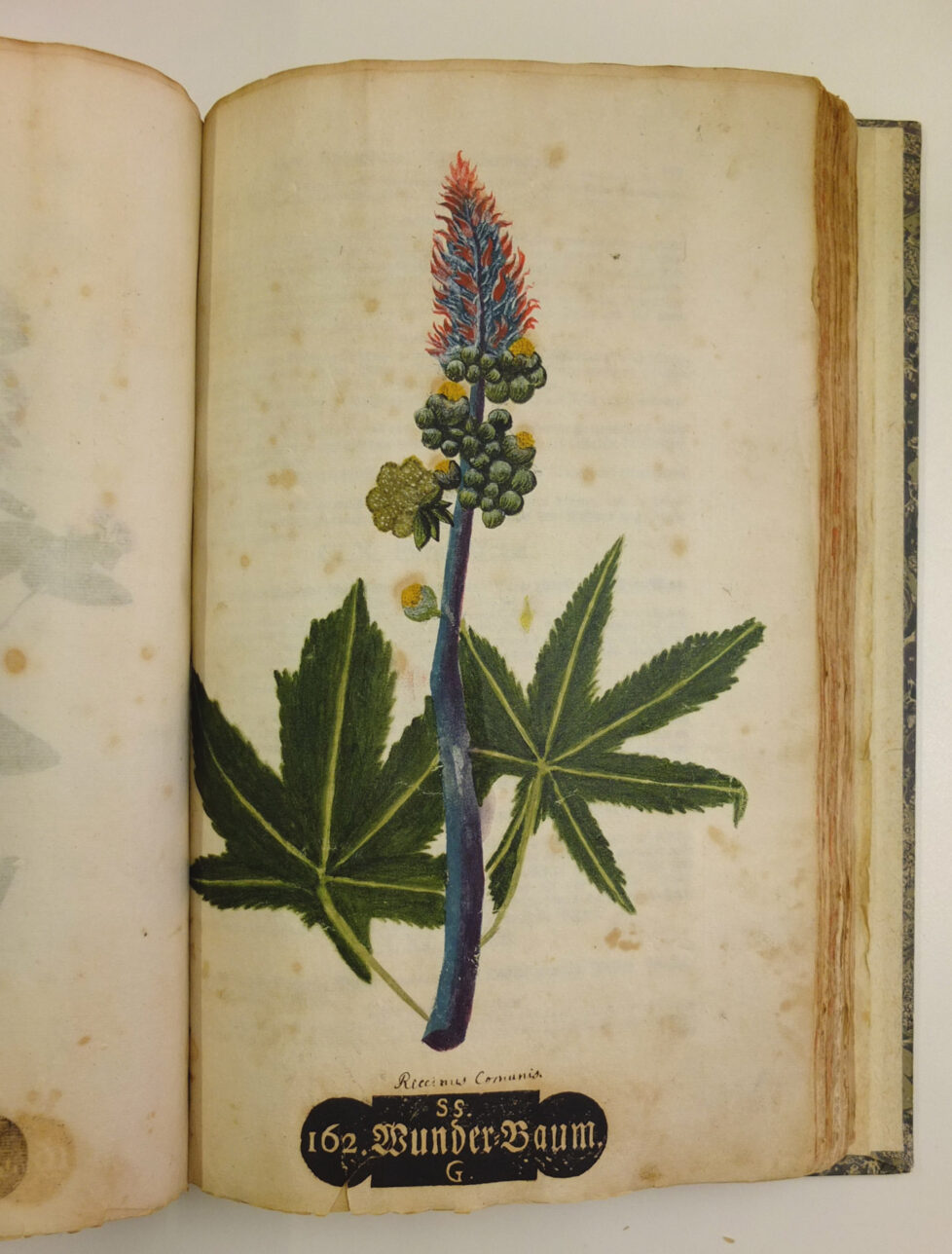

Nature self-printing (Naturselbstdruck) is a printing technique that consists in pressing the coloured surface of an object directly onto paper, hereby imprinting the page with a distinctive, non-reproducible image. Over time the repertoire of such “contact images” has grown to include a broad variety of motifs—from lace borders to fossils and rocks, to bat wings and snakeskin. Botanical studies is where nature self-prints are most commonly found, as evidenced by a series of historical publications held by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin: the magnificent folio Botanica in Originali (1733) by Johann Hieronymus Kniphof; Ludwig Christian Gottlieb’s Ectypia Vegetablium (1760); Constantin von Ettinghausen’sand Alois Pokorny’s Physiotypia Plantarum Austriacarum (1856); and William G. Johnstone’s The Nature-Printed British Sea-Weeds (1860). The success of nature prints obtained from pressed plants was due to the fact that, unlike traditional herbaria, they were not particularly susceptible to humidity and mould; for this reason, as early as the Modern Age they began being deployed as an alternative to herbaria. The same is true of other media: in comparison to drawings and copperplate prints, nature prints excel in the accurate reproduction of nature, seemingly conveying an undistorted image of the natural world. The intensified pictoriality and higher degree of authenticity of nature prints was belied to stem from the physical contact of the plant with the image carrier. Resemblance through touch was interpreted as a form of “self-registration” operated by nature: it was the plant itself that generated its self-image by imprinting its very material traces on paper. In his book Ähnlichkeit und Berührung (1999), Georges Didi-Huberman conceives of printing (Abdruck) as the paradigm of an “archaeology of similitude,” for its capability to nullify the distance between the object and its representation. In this light, nature prints are envisioned as blind copies of that which exists in nature.

Moths and Butterflies starts exactly with this claim: that the great diversity of butterflies should be presented as it appears in nature. As Denton specifies in the book’s preface, his goal is to present native butterflies and moths in all their freshness and grace, as they appear in the woods and fields—rather than as dried and mutilated specimens pierced to a display case or as fragments dissected for scientific purposes. What he obviously had in mind in his critique were the large-scale collections of butterflies and moths found in 19th-century natural history museums, where exemplars were typically needled and preserved as relics. However, the entomologist’s concern with the presentation of naturalia should also be seen in the context of his own research in natural history, as well as his artistic activity. The Denton family’s passion for collecting was legendary: Sherman and his three younger brothers used to accompany their father, the geologist William Denton (1823–1883), in his expeditions to Australia, New Zealand, and New Guinea in search of objects of natural history. After their father died during an expedition, the Denton brothers had to find ways and means to professionalise their collections, which included fossils, bird eggs, fish, snake skins, insects, stones, and butterflies. With the foundation of the Denton Brothers Company, they were able to turn their passion for collecting into a thriving business. Sherman Denton significantly contributed to the success of the international trade of preserved butterflies by developing a plaster holder for the display of lepidopterans, which he patented in 1894. The so-called “Denton mount” replaced brutish forms of impaling with a sophisticated mounting that sustained the delicate butterfly bodies. Thanks to their exquisite appearance, Denton’s creations were soon sought after all over the world. Not only that: at the 1900 Paris Exposition, the Denton Brothers won the gold medal for their innovative displays of butterflies—whose subdued beauty and fragility stood out amid the monumentality of the show.

Regarding the question of pictorial representation in Moths and Butterflies, it is important to keep in mind that Sherman Denton was not only a successful dealer, but also a talented self-taught painter, draftsman, and taxidermist. In the late 1880s, the U.S. Commission of Fish and Fisheries at the Smithsonian Institute hired him for the conservation of zoological specimens. Since drying fish scales tend to quickly lose their coloration, Denton made detailed watercolours and drawings, which he eventually used to create lifelike models. His motivations were made clear in the promotional pamphlet Fish Mounting as an Art, where he claimed that a stuffed fish was the “ugliest thing in the way of decoration one can find” and that “when gazing on the dried and wrinkled skin without beauty of form or color, how difficult it is to realize that this wretched object was once a graceful, glittering fish!” Denton eventually discovered and patented a specific preservation technique to retain the natural colours of prepared fish, and became the leading producer of fish taxidermy for collectors and museums. Among his clients were the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, the Field Museum in Chicago, and the Agassiz Museum at Harvard University. Denton was also entrusted with the creation of illustrated annual reports for the New York Fisheries, Game and Forest Commission; to this end, he produced brilliant watercolour artworks as templates for chromolithographs.

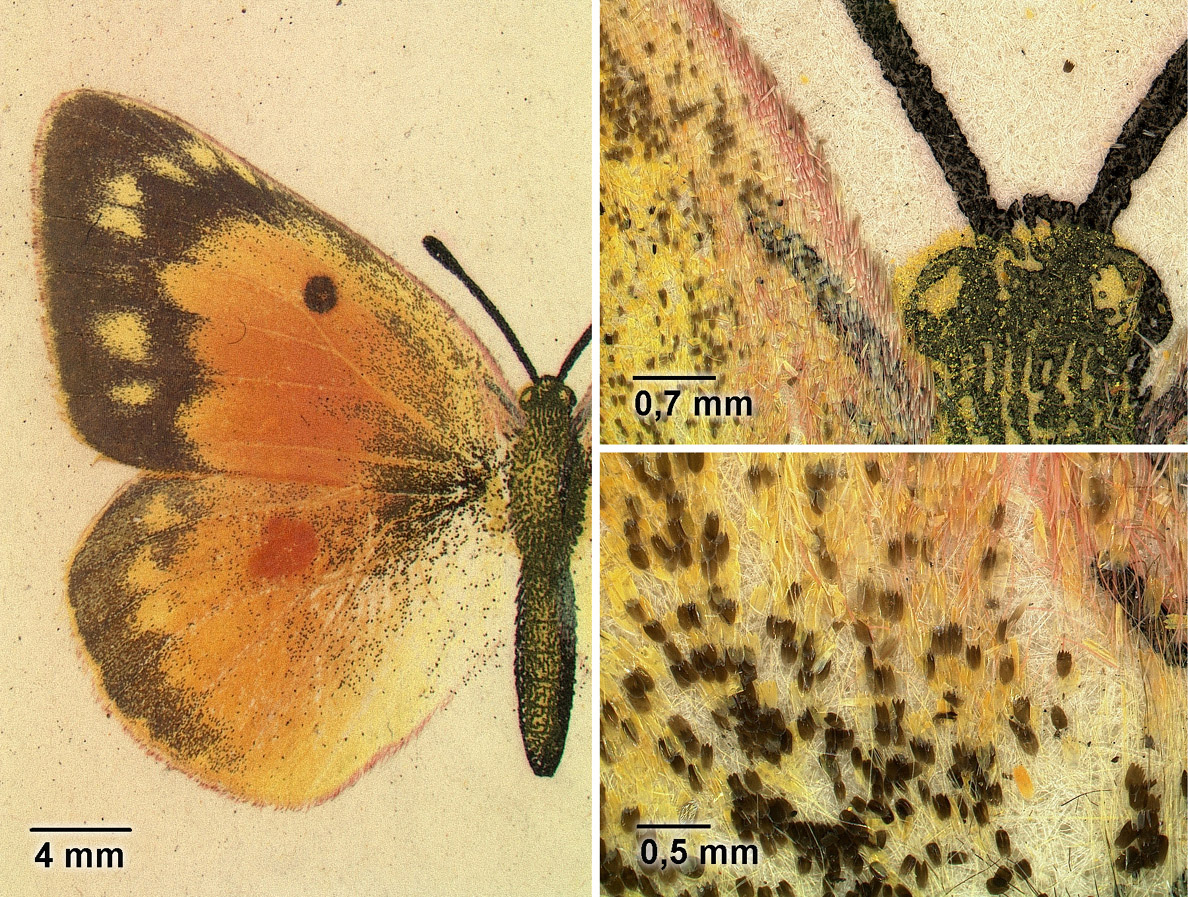

The use of nature printing to immortalize native species of butterflies followed a logic for which images “take the place” of nature, a logic well in line with the dominant aesthetic discourses in the 19th century. Grappling with the conflict between nature and art in every new conjunctures since antiquity, the attribution of a life force to the representation of an object has been fuelling the illusionary machine of art for centuries. The distinctive feature of nature prints in Denton’s Moths and Butterflies, however, lies in the way in which the imagination and the materiality of the natural object intertwine: unlike common nature prints of plants, here it is not the printing ink that produces the direct copy of nature, but the immediate transfer of the wing scales onto paper. Thus, the liveliness of the representation emanates from the quasi-living texture of the material, which preserves the iridescence of the pigments in a way the printing ink cannot do. This effect is obtained by sticking the scales of the imprinted butterfly wings onto a preparatory surface coated with a thin layer of glue made from gum Arabic, tragacanth, and fish bladder. The butterfly bodies and antennae are printed from copper engravings and then coloured by hand in fine brushwork. As proved by the photomicrographs of the Senckenberg Society’s German Entomological Institute, the butterfly wings impressed in paper consist of the delicate scales of the moths along with their colourful pigment deposits.

In his remarks, Denton makes the point that he has not invented the technique of butterfly printing; he has simply contributed to its refinement. The first experiments with this technique can indeed be traced back to the inventor of the sottobosco painting, the Dutch painter Otto Marseus van Schrieck (1613–1678). The subjects of his paintings were forest still life and the microcosm of the forest ground, teeming with snakes and toads, grasshoppers, dragonflies, mice, mushrooms, and forest flowers. Instead of painting butterflies and moths, van Schrieck would transfer their scales directly onto the canvas—a conservation technique called “lepidochromy.” Starting from the 18th century, this became a common practice in entomology for it enabled the faithful reproduction of the iridescent colours and texture of the wings’ scales. The procedure was described in detail by 18th– and 19th– century lepidopterists such as Henri Poulin (19th century), George Edwards (1694–1773), and Ernst Vanhöffen (1858–1918). Between 1900 and 1912, the same technique was used by Caribbean naturalist Théophile Raymond (d. 1922) in his countless watercolours of Venezuelan butterflies. Today lepidochromy is rather rare; few examples can be found in the collections of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, the Musées Grand Estin Nancy, and the Höhere Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchanstalt in Vienna.

The exhibition catalogue of the Third German Arts and Crafts Exhibition, held in Dresden in 1906, emphasized how the animal world, “namely that of the lower organisms (butterflies, insects, fish, also birds) was [is] also being eagerly studied in order to draw inspiration from it in colour and form for the design.” After all, Denton had the decorative arts in mind when he suggested that the publication of Moths and Butterflies be a source of inspiration for artists and decorators. The book has to be seen in the context of several original works that, from the mid-19th century on, had opposed the habitual copying of historical patterns as a source of artistic inspiration in favour of celebrating living nature. “One need only use one’s eyes,” Denton argues, to recognize the potential of the flora and fauna on one’s doorstep—a method to escape the epigone-like lack of originality. In the extensive collection of photographic originals at the Berlin University of the Arts, the most prominent of which are Karl Blossfeldt’s (1865–1932) plant photographs, is a series of photographs of butterflies mounted on cardboard; these images show that the motif of the butterfly was part of the repertoire of decorative art originals. Fashion designer Jean-Charles Worth (1881–1962) is said to have taken inspiration for many of his dress designs from Denton’s butterflies on display at the World’s Fair in Paris. Other examples, such as the inlaid works behind glass preserved at the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin, testify to the process of image-making of butterflies through their natural substance. As early as the Biedermeier period, colour-coordinated bouquets and floral patterns of butterfly wings and fish scales were arranged in a similar manner.

For Moths and Butterflies, Denton collected 50,000 butterflies and processed them as visual material—an undertaking that breathes the spirit of the fin-de-siècle and should be viewed against this historical background. In his preface, the author emphasizes that “in collecting such a large number of specimens, many new facts in regard to the habits of these charming creatures have been observed (…).” His aim was therefore not only to depict the wonderful beauty of the butterflies, but also to document their lifecycle through descriptive accounts. The abysmal fragility of this understanding of vitality was already inscribed in the late 19th-century sensibility, if we consider that collections of objects from nature preserve that which is disappearing. Today’s reader might be seized by a peculiar sadness when looking through Denton’s volumes, as if standing in front of rows of impaled butterflies in a museum of natural history. In view of the rapid species extinction, the discourses on man-made destruction of nature, and the struggle for ecological and multispecies balance, the traces of life that these delicate creatures bear come off as legacies of our culture: they are relics of a natural world that has disappeared. This opens another chapter on Denton’s extraordinary publication, that is, the long tradition of nature dying for the sake of art. In the same tradition stands, for example, the practice of direct casting of animals and plants, which involves the pulverization of the object used in the process. As Robert Felfe has shown in Naturform und bildnerische Prozesse (2015), in the early modern period this creative process was highly ritualized: the animal or plant was placed in a wooden box for casting—a “small coffin,” as it was called; after the negative mould had hardened, the natural components of the cast object were completely removed from the mould by pulverizing their remnants in a process of annealing, or burning out, which prepared the mould for metal casting. At the end of the procedure, the artist’s breath was used as a life-giving element to clean the hollow mould of the ash residues. The resulting works, therefore, do not lament the loss of nature; rather, the creative process allows the creature that was cast off to resurrect in a new form.

The prints of illustrator John James Audubon (1785–1851), who, according to his own account, shot up to a hundred birds a day to produce his magnificent depictions, may also be read in such fashion. To create his images, Audubon would bring his models into the desired position with a wire frame. This cultural practice has been not least addressed by modern art, as illustrated by one of Jean Dubuffet’s (1901–1985) most trenchant statements: “It is typical of culture that it cannot let butterflies fly. It does not rest until they are pinned and labelled. The original, massed teeming, the fertile humus on which a thousand flowers can grow, is not cultivated by cultural propaganda.” In short, art produces dead butterflies, and the appearance of being alive is only an illusion. Dubuffet’s own collages of butterfly wings undoubtedly reflect this artistic furore of aestheticizing nature.