Field Notes, Historiography, Plants, Practices, Spatial Orders

The Transnational and Interdisciplinary Journey of Gärtnerisches Planzeichnen

Villa Parey was built in 1895–1896 as the family house of Paul Parey, founder of the publishing house Paul Parey Verlag. The company was unrivalled in the fields of agriculture, horticulture, forestry as well as plantation technologies, with some publications relating directly to the colonial project of the Kaiserreich. Others had more unexpected effects on landscape history and urban gardening, as in the case of Max Bertram’s Gärtnerisches Planzeichnen (1891) in Meiji Japan.

18.03.2022

The building known as Villa Parey, part of the complex of the Gemäldegalerie in the Kulturforum Berlin, today accommodates the institutional spaces of the 4A_Lab. The villa was built in 1895–1896 as the family house of Paul Parey, founder of the publishing house Paul Parey Verlag. As an unrivalled publishing company in the fields of agriculture, horticulture, forestry, and plantation technologies, the Paul Parey Verlag produced numerous books and magazines related to plants—the 4A_Lab’s current research theme—including the two-volume book Gärtnerisches Planzeichnen (EN: Garden Plan Drawing) in 1891. Authored by Max Bertram (1849–1914), the co-founder of the Association of German Garden Artists (1887) and the Horticultural School in Dresden (1892), the book was initially conceived as a guide to drawing techniques and drawing templates for gardens and parks. Although Bertram is a less prominent figure in the history of German landscape architecture in comparison to personalities such as Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell (1750–1823) or Peter Joseph Lenné (1789–1866), his manual is remarkable for its transnational and transregional framework and its interdisciplinary approach to garden art.

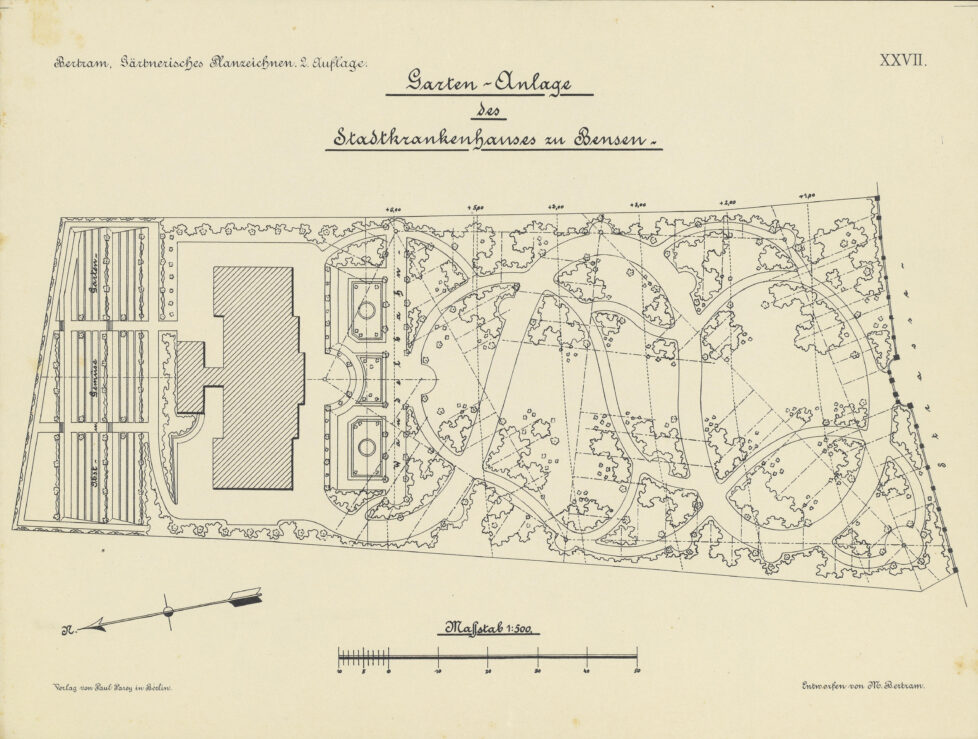

The transregional approach of Gärtnerisches Planzeichnen is evident in the range of case studies examined: the thirty-nine plates in the volume illustrate gardens and parks that are located well beyond the boundaries of Dresden and the Saxony region, where Bertram served as a member of the artistic advisory board of Saxon King Albert (1828–1902). Covering various regions, including present-day Poland and the Czech Republic, the case studies help us envision the geographical boundaries of German garden culture in the 1890s. Bertram presents, among others, the plans for a park in Konitz, Prussia, and the garden of a municipal hospital in Bensen, Bohemia.

Despite what the title suggests, the disciplinary focus of Gärtnerisches Planzeichnen is not limited to garden art. The subtitle of the book includes the term Landschaftsgärtner (landscape gardener), implying that the book touches on the subject of landscape architecture, too. Significantly, Bertram—who considered the garden as an element of urban planning—chose to describe himself as a Garteningenieur, or “garden engineer,” rather than “gardener” or “garden designer.” Also significant is that, after the publication of this volume, the word Landschaft (landscape) was adopted in the naming of the newly established “Government Office of Natural Landscape Management in Prussia” (1906) and for a study program in landscape planning at Berlin University (1929). This demonstrates that Gärtnerisches Planzeichnen can be counted among the works that were flourishing at the peculiar intersection of garden art and landscape architecture in late nineteenth-century Germany.

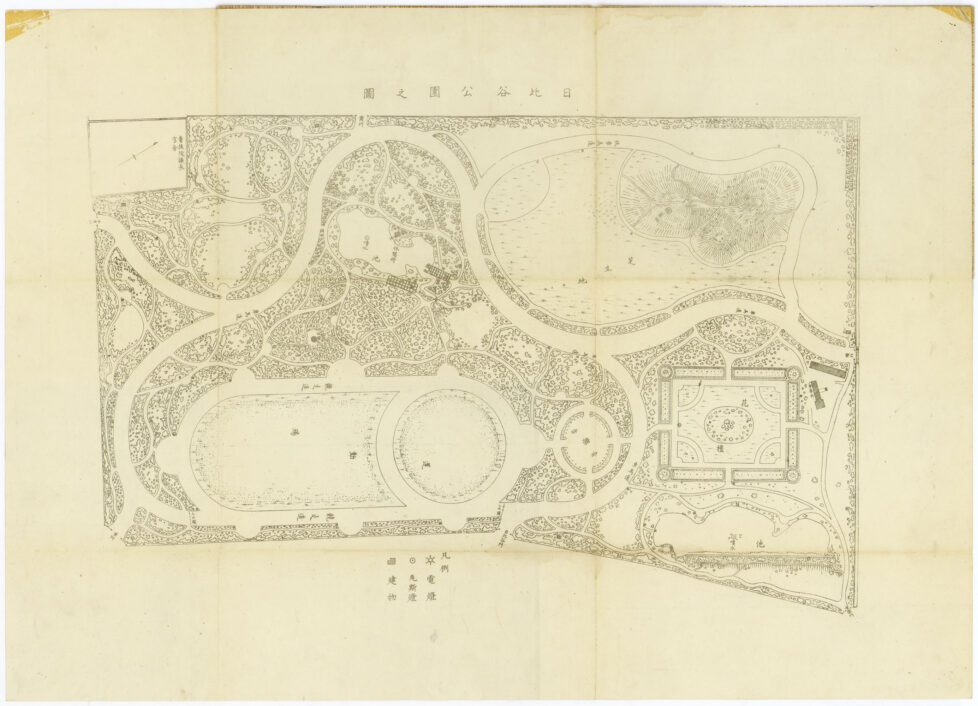

The book has an interesting history of circulation along transnational routes: in 1900, Japanese landscape architect Seiroku Honda (1866–1952) brought it to Japan and used some of its templates for the planning of Hibiya Park—the first Western-style park in the country (1903). Honda selected some patterns from the book’s garden plans and brought them together to meet the demands of the Council of Tokyo, which aspired to create a Western-style park in the city. This is how the volume gained unexpected popularity in Meiji Japan as a Western—not specifically German—park design book. Interestingly, we can see how, as it travelled from Germany to Japan, the publication became representative of a broader regional context than just Prussia and its neighbouring regions, for which it was initially intended.

The book is also crucial to an understanding of the multidisciplinary roots of landscape architecture in park planning and forestry in early twentieth-century Japan. While studying in Germany (1890–1892), Honda showed interest both in forestry and urban parks. In 1900, he started teaching landscape architecture at the Department of Forestry of the Imperial University of Tokyo—becoming the first professor to host a chair in this discipline in Japan. Later on, he came up with the concept of “forest parks” as the park system in Japan and Korea, i.e. forests surrounding cities as parks. Although further research on the implications of Gärtnerisches Planzeichnen for Honda’s forest park designs is needed, it is certain that the book provided a source of inspiration for the design of the “Western-forest” in Hibiya Park’s plan: with its meandering paths and tree arrangements, the forest in the southwestern section of the park plan is a direct translation of the landscape of Plate no. 32 in Gärtnerisches Planzeichnen.

Today, WorldCat shows a significant geographical and institutional distribution of Gärtnerisches Planzeichnen across the globe. Copies are currently found at several locations in Germany and Europe (mostly in countries at the border with today’s Germany) as well as the U.S. The typology of hosting institutions is also rather diversified, ranging from university and national libraries to research institutes and even a botanical garden. As an example of the transnational, transregional, and interdisciplinary journey of the theory and practice of garden art/landscape architecture at the turn of the twentieth century, Gärtnerisches Planzeichnen invites us to explore the geographical breadth of German garden culture; the blurred boundaries between garden art and landscape architecture or forestry; and, most importantly, its acculturation over sociocultural boundaries and its unforeseen influence on the landscape of a foreign country as distant as Japan.